Slocan, developed in the 1890’s mining rush, is only about 1/2 hour from New Denver or 8 1/2 hours east of Vancouver, BC. It sits at the entry to Valhalla Provincial Park.

Slocan is a Native word that means to ‘pierce through the head’. Presumably this is in reference to the traditional Aboriginal way of fishing the plentiful salmon indigenous to the area.

The roadway to Slocan winds across the mountains, providing spectacular views of the valley.

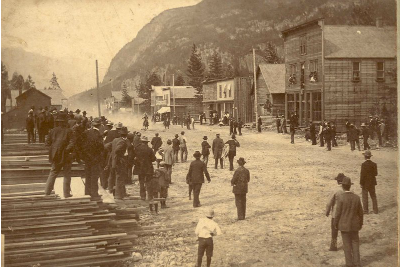

By the state of it now, it is hard to imagine the town was ever booming enough to earn the title Slocan ‘City’.

Bustling Slocan City. Photo source; http://www.slocancity.com/history/

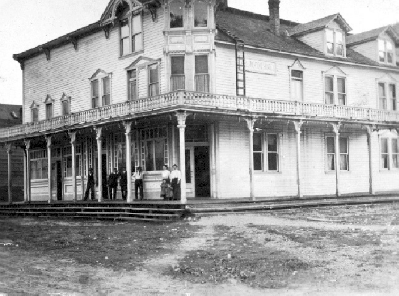

It was here that famous Canadian David Suzuki and his family were interned, in the now disappeared Arlington Hotel. It had already been abandoned for 20 years or more by the time they arrived. He wrote in his autobiography:

‘We were among the first contingent to arrive in Slocan City and got to live in the hotel closest to the lake. We had a small room on the second floor at the back of the building. It must have been a grand building in its day – a large porch ran all the way around it, while columns supported a similar porch above it. But the boards of the porches were so weathered and rotten that we weren’t allowed to run around on them . . . Our building was filthy and cramped . . . We quickly took it for granted that in the morning we would wake up covered in bedbug bites.’

There is plenty of information about the history of the Arlington Hotel at slocancity.com, including all known previous owners, some interesting events that took place there, and even record of all known deaths to have happened on the premises.

Author Joy Kogawa, writer of acclaimed 1981 novel Obasan which is partly set in Slocan, was also interned here. In Obasan, p. 105, there is a “letter” entry from May 14, 1942:

‘Aya, kids, Dad and I have decided to go to Slocan. We hear that’s one of the best ghost towns.’

In the 1970’s she wrote to the government asking that a memorial be set up. The reply she was given at the time was that ‘the government preferred not to remember those events’.

To her though, it was the exile afterwords that was the most inhumane. Her first published work was about a little boy who moved to the Prairies but wanted to return to the mountains.

According to the nelsonstar.com, Joy says;

“That was my story. I loved Slocan. Apart from the feeling of prejudice that did exist here, the mountains, trees, grass, lilies, fiddleheads and mushrooms we picked — all of that I loved.”

Joy Kogawa was amongst the crowd that gathered in June of 2012, when permanent memorials were finally erected in the Slocan Valley.

Wikipedia says that the population here is just under 300, I would have thought it to be much less.

Though there is plenty of history here, not much of it physically remains. There are not many buildings in town, historic or otherwise.

The kindergarten building is the only from that time that was not destroyed, and it has not been in Slocan for many decades. It was relocated to a place named Coaldale in 1946.

It is not easy to find specific details about Slocan City internment history. How many people were sent there? We know it is said to have had an ‘alien processing centre’.

It is interesting to see the different ways former internment towns choose to deal with their history.

Some embraced theirs, built fantastic memorials, welcomed back former interns – even treated them well enough that they chose to stay in the first place – while others all but erased every sign and reminder of the terrible time.

Perhaps Joy Kogawa was correct in saying that the greatest injustices happened after the war, when even the families that had managed to stay together during internship, were sent across Canada to places they did not call home. Separated from friends and family – never to see each other again.

Families and loved ones were torn apart from the beginning to the bitter end of the war. We now know that so many never recovered. Children never saw their fathers again, wives their husbands. Communities that had economic and social strength were obliterated, a generation of Canadians that would remain lost and separated.

And it would not be insincere to ask, why?

From japanesecanadianhistory.net:

Prime Minister Mackenzie King declared in the House of Commons on August 4, 1944:

It is a fact that no person of Japanese race born in Canada has been charged with any act of sabotage or disloyalty during the years of war.

On April 1 1949, the restrictions were lifted and Japanese Canadians were given full citizenship rights, including the right to vote, and the right to return to the West Coast. But there was no home to return to.

The Japanese-Canadian community in British Columbia was virtually destroyed.

It should also be known, as a final injustice, that the Japanese paid for their own internship. It was their monies – pooled together – that were drawn from to support the internment and work projects.

And so you know, Canada’s government would like us all to stop using the word ‘interned’ when referring to what happened to the Japanese in WWII.

They say it was more of an ‘exile’ than an internment. According to the government, they officially only interned 36 Japanese.

The rest were sent to live in remote exile.

Additional photos in the slideshow.

Follow our tour of British Columbia’s WWII internment towns in the ‘WWII Japanese Internment‘ section, or head to the Habitual Runaway on Facebook for more photos.

Related articles

- Slocan Internment Sites Commemorated (nelsonstar.com)

- Slocan City History (slocancity.com)

- The Arlington Hotel (slocancity.com)

how do you manage to secure these historic photos. thats amazing.

LikeLike

…Just photo sourced & linked them after a lot of research :D.

LikeLike