Like most everywhere on the planet, Canada has its own abysmal history. Perhaps the darkest stain on our record occurred during the WWII Japanese internment.

Japanese persons began immigrating to Canada early in the 19th century – despite our blatant fear, racism and discrimination toward them.

At the time, we were also intolerant of Jewish persons, and persons of colour. These groups were banned from voting, and prevented from entering certain forms of employment. They were primarily ineligible for social assistance and all but barred from fishing and hunting.

The hope was that we would push the foreigners out, forcing them to return to their homeland.

Canada was so discriminatory against the Japanese, that we formed the The Anti-Asiatic League in 1907. Made up of primarily white business owners, the purpose of the ‘League’ was to force limits on Asian immigration.

The Japanese were seen as fierce competition in agriculture and fishing sectors.

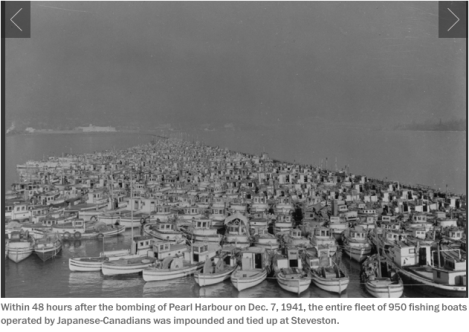

Photo source; http://comrademcbotbyl.tumblr.com

After the bombing of Pearl Harbour in January 1942, Japanese-Canadians were branded as enemy aliens under the War Measures Act.

On 14 January 1942, the government passed an order calling for the removal of male Japanese nationals 18 to 45 years of age from a designated ‘protected area’ 100 miles from the BC coast.

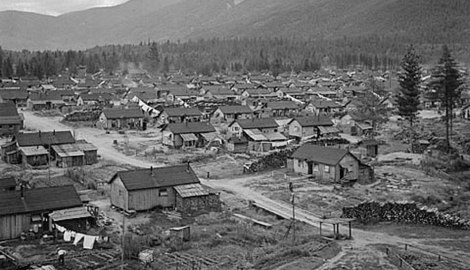

Photo: http://www.yesnet.yk.ca

At first, these men were primarily sent to ‘road camps’ throughout British Columbia.

Many men (and boys) perished from sickness and starvation while building roads connecting communities through rural mountainous BC.

Photo source: http://forums.castanet.net

Just three weeks after the first, another order was given to allow the removal of “all persons of Japanese origin”. At least 27,000 people were detained (women and children), and their property confiscated.

They were made to believe that their homes and valuables would be returned at the end of the war, but of course that did not happen.

Photo: http://www.windsorstar.com

Homes, fishing boats, vehicles, businesses – family heirlooms – everything. Taken and sold for a pittance to the local whites.

Photo: http://www.windsorstar.com

Men drove the family vehicles to a downtown Vancouver stadium, parked, handed their keys over to a white man, and entered the crowded, stinking stadium to wait with thousands of other Japanese to be taken away to camp.

Photo source: http://www.windsorstar.com

Many children were brought up in these camps, including famous Canadian environmental activist, David Suzuki. David was a third-generation Japanese-Canadian.

In June 1942, the government sold the Suzuki family’s dry-cleaning business, then interned Suzuki, his mother, and two sisters in a camp at Slocan in the British Columbian Interior.

Photo source: http://www.windsorstar.com

Not all men were sent to internment camps and road crews.

Some were shipped for labour on sugar beet farms in Taber, Alberta, others were sent to work on a logging operation near D’arcy, BC.

In the Lillooet valley, Japanese men found work on the railway, in local stores and on farms. In the Okanagan, they were put to work in the orchards.

Photo source: http://app.ufv.ca

Some lived in unsanitary stables and barnyards, through freezing winter – and hell hot summer. In a few cases, conditions were bad enough that the Red Cross stepped in and redirected food rations meant for Canadian civilians affected by the war, to the starving Japanese.

Various camps in the Lillooet area were labelled “self-supporting projects” (or “relocation centres”). These housed middle and upper-class families deemed less a threat to public safety.

Though not technically ‘interned’, the Japanese here faced restrictions on their movement, but were able to live a somewhat ‘normal’ life with their families. They worked, operated shops and had children in school.

Photo from http://www.windsorstar.com

However, their children could only attend certain schools, and they could not leave the boundaries of the “relocation centre” without permission.

At the end of the war, interns were given a choice. Move east or go back to Japan. Many Japanese-Canadians (born in Canada), chose to head to Ontario – where they faced further discrimination.

There are many stories of successful business owners, teachers and doctors being forced to Ontario to work as farm hands – one of the few employment options they faced.

Other Canadian born Japanese were forced to relocate to Japan – an unfamiliar foreign place, with a language they didn’t speak, and food they had never eaten. Many stories have been written about this uncomfortable process.

Truly, Canada played a big hand in contributing to an already dark WWII history. Though we finally made apologies (by 1988) and nominal financial retribution (on-going) for our part in the former laceration of Canadian-Japanese life, in some cases, the wounds are still healing – and others will never mend.

Additional photos in the slideshow.

The upcoming articles are of a recent (photo rich) tour of ‘Canada’s (former) Japanese Internment Camps’ (CJIC).

You can follow our tour in the ‘WWII Japanese Internment‘ section, or head to the Habitual Runaway on Facebook for more photos.

(continued)

Related articles

- Japanese Canadian Internment (Wikipedia)

- Internment Then and Now (najc.ca)

- Photos: BC’s Dark History of Japanese Internment (windsorstar.com)

- The Politics of Racism (japanesecanadianhistory.ca)

- Internment of Japanese-Canadians and Japanese-Americans (ww2db.com)

My mother grew up in Vancouver during the war. She remembers their Japanese-Canadian neighbour coming to say goodbye to her mother because he was being sent to an internment camp. She remembers him telling my grandmother that he had fought for Canada in World War I. It is a shameful part of our past, for sure.

Have you seen the documentary Obachan’s Garden? It’s about a Japanese woman who came to BC as a “picture bride” and who was forcibly relocated along with her family in WWII. You can still visit her house and garden in Steveston.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ugh – that cave me chills – and made me feel a bit like crying!

How awful to have fought for our country just to be imprisoned and have everything you worked for taken away. To have to leave your close friends and neighbours to live in horror. Just awful.

I have NOT seen the documentary – but now that you have pointed it out to me, you know I will – and I am in Steveston almost weekly, so I will absolutely look into that.

Thank you!!

LikeLike

My mum said the man was crying. And no wonder.

Warning: I cried through much of the documentary! Here’s a link to the NFB site where you can watch it. (Try not to read the synopsis directly beneath the video, if possible, because annoyingly it gives away a surprise.)

http://www.nfb.ca/film/obachans_garden

LikeLike

Oh thank you Leslie …for the warning & spoiler alert too.

I will save it for a moment when I am ready for a good cry!

LikeLike

Man that is just so wrong. Nothing more I could say about it.

LikeLike

How sad. These days it’s hard to believe that people could have thought they were doing the right thing then.

LikeLike

I know, it blows my mind. So very sad. People justify crazy things in times of war. I try to picture myself living during this era and just can’t imagine what it would have been like…

LikeLike

I think Ana is right. We just can’t imagine what life would have been like in another era – even when the era was so close to our own, and our parents or possibly grandparents lived through it. That doesn’t justify what was done – fear makes people do cruel and inhuman things. Which brings up a question. Is cruelty caused by fear? Was the internment caused by people’s fear or just plain meanness? Or did they play off each other? What do normally “nice” people – like me – do when threatened? What would we do if the shoe was on our foot, and we had to survive? What a great article! Sad, but thought-provoking!

LikeLike

Oh yes Marsha – I cannot and do not want to ever imagine what it might be like to live through war time (fingers crossed).

I do think cruelty can be a result of fear (I don’t think it was ‘mean-ness’ at all).

A small example; when I was in Thailand & had a giant bird eating spider in my bathroom, I did not even want to look at it, I had to kill it. Purely out of fear. The Thais would have captured it and released it outside (understanding that it too had its place in nature), but I was terrified – I HAD to kill it (and it was not easy to kill – it was very gory *ugh*).

Fear makes us react to ‘save our lives’ – even when the situation is not life or death.

Later it was deemed that the Japanese-Canadians were never a threat to our national security – but that didn’t matter at the time. It was all about perceived survival.

Just so, so, so sad.

LikeLike

I live in that area of California that interned it’s japanese citizens as well. Several families farmed their neighbors’ farms, and when they returned from the camps, their possessions and farms were still in tact. I’m afraid that wasn’t the norm, though. Our county office, where I used to work, invited three former internees to come to speak to the kids this year. It was fabulous, but sad, of course. The good part is what they ended up doing with their lives. 🙂 Marsha 🙂

LikeLike

OMG, I soooo loved this post. you actually wrote out such incredible history narrative just like as if i was listening to a curator in a museum tell the story.

LikeLike

Oh thank you – what a lovely compliment!

I was all ‘fired up’ when I wrote this one. I spoke about it AT my husband for hours after posting :P. He is WWII Internment Camp saturated! 🙂

LikeLike

I agree so much with larkycanuck . This is so well presented…such a gripping narrative. I too feel as though I’ve been through a museum with a curator and duly paid homage. Thank you so much!

LikeLike

You are too kind!! Thank you 😀

…Now that is a job I would love actually…..

LikeLike

My mother still remembers as she and her entire family were corralled at Hastings Park. It stank…the cubby holes that they stuck entire families into were ripe with the smell of animal fecal matter. After all Hastings Park (the Agricultural Barn) was used as a horse-barn before they interned the Japanese there prior to shipping them out to the camps.

Yes, there is a lot of resentment there still seething inside me as I write these words. My Irish-American wife (who lives up here in Surrey with me) wrote a college-report on the linguistic after-effects of the Japanese-Canadian internment for her linguistics class. Most Japanese-Canadians now don’t speak a lick of Japanese – and the internment is partly to blame. The internment forced Japanese-Canadian families to seriously look at blending into the community to the extent that they could (given their skin color). The internment is a part of family history.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your comment. I love learning more about current perspective on the atrocities of that time. I simply cannot imagine how it would have been to have lived through that. Unsurprisingly there were dramatic consequences for descendants as well. Not many of us think about how internment changed lives generationally. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

We watch documentaries about the Holocaust and think we would never have persecuted the Jews or stood by and let it happen. But we did, didn’t we? We interned Japanese, sold their homes, businesses, and possessions. No difference. I am reading France’s Itami’s beautiful book REQUIEM and searched for information about the internment camp at Lillooet BC. Thank you for this story. It provides the historical background to the novel.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Dash by Kirby Larson — Book Recommendation | By Word of Beth·